In an era defined by the Washington Naval Treaty, the 8-inch gun cruiser was by far the most favoured intermediate ship in the US Navy (USN). All that had to change when the London Naval Treaty restricted the construction of 8-inch gun cruiser by numbers. If the USN wanted to build more cruisers in the future, the majority of them had to be light cruisers. The pursuit for a light cruiser that would rival the heavy cruiser began, leading to a series of design studies that proposed various solutions to implement effective protection and armament, some of which are considered by many today as unconventional or even outrageous. Although not officially drawn up as a preliminary design, USS Grand Rapids represents a historical footnote in design studies that would eventually lead to the construction of the Brooklyn class cruiser in 1934.

Dimensions: 186.5 m overall length; 17.8 m beam; 6.5 m draft

Machinery: 4x shaft geared turbines; 8x Babcock & Wilcox boilers; 91,000 shp @ 32.5 knots; range 10000 nm @ 15 knots

Armament: 15x 6-in/47 (5x3); 8x 5-in/25 (8x1)

Aircraft: 4x with 2 catapults available

The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 brought a series of shipbuilding restrictions as an attempt to prevent a naval arms race. Cruisers in particular were each limited to a maximum displacement of 10,000 tons and a gun caliber of 8 inches. No limits were imposed on the number of cruisers that could be built at this time. The 8-inch gun cruiser was seen by the USN as the favourable type of ship for operations in the Pacific with continual improvements to the design evident across the Pensacola, Northampton, Portland and New Orleans classes. The unrestricted quantity of 8-inch cruisers came to an end in 1930 when the London Naval Treaty was signed. There would now be a clear distinction between “types” of cruisers based on their gun caliber. Cruisers armed with guns up to a caliber of 6.1 inches would be considered “light” cruisers while “heavy” cruisers could be armed from that caliber and up to 8 inches. Furthermore, both light and heavy cruisers would each fall under a total tonnage limit shared across all constructed ships of that type while heavy cruisers would be further limited by numbers. This left the USN little room to further construct the 8-inch gun cruiser they favoured and had little choice but to explore the options for a capable light cruiser that would satisfy the limitations set by the treaty.

Shortly after the Senate approved the London Naval Treaty of 1930, the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R) began a study on 6-inch light cruiser designs. The initial basis was a ship that matched the speed and cruising characteristics of the New Orleans class as closely as possible. In terms of armament, the USN desired the new ships to have as many guns as necessary to compete with heavy cruisers while retaining enough armor for an "immunity zone" against 8-inch shellfire. The first design “Scheme 1” proposed an arrangement of fifteen guns in a mix of three quadruple and one triple turrets. This was quickly rejected due to a lack of certainty that the quadruple turret would be successful. An arrangement of four triple turrets was favored in Scheme 2, a 9,600-ton design that was viewed to have enough firepower for a 6-in cruiser while having satisfactory protection against 8-inch guns. A significant feature of later designs based on Scheme 2 was the positioning of the aviation facility at the far aft of the ship instead of amidships like the earlier heavy cruiser classes. This would make floatplane recovery easier as well as minimize interference with other activities occurring around the superstructure.

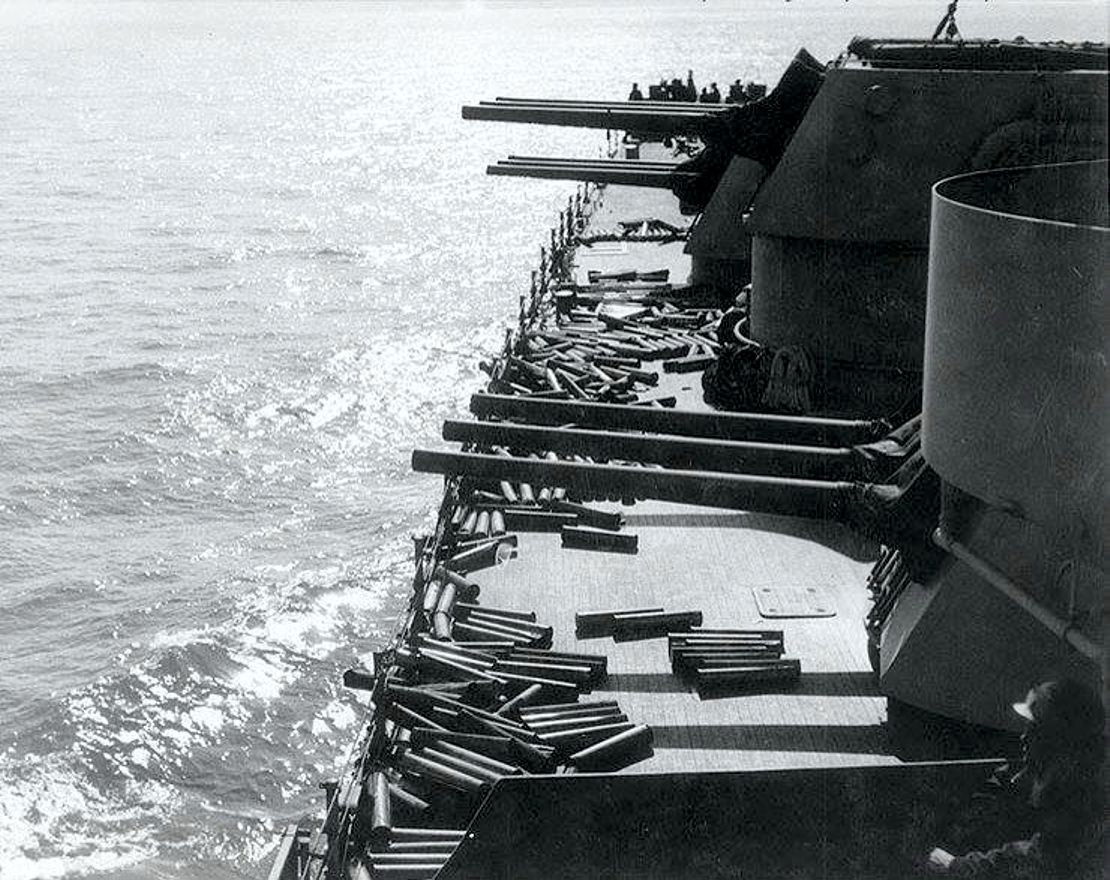

The general concept of balanced armament and protection that stemmed from Scheme 2 would have satisfied the USN, had not Japan announced the construction of the Mogami class with fifteen 6.1-inch guns on only 8,500 tons. In reality, the Mogami class would exceed the treaty limit by over 1000 tons after undergoing construction to fix serious hull defects, but the USN had little knowledge of the exact characteristics of the ship at that time. The balanced twelve-gun design of Scheme 2 no longer seemed satisfactory against the new Mogami class. In 1933, fifteen and sixteen gun designs were drawn up at the expense of protection, taking into account that the latest 6-inch shell had more than 1.5 times the penetration of the older shell. This meant that the value of the 6-inch gun increased while the effectiveness of armor measured against the older shell would decrease. The need for an immunity zone against 8-inch shells was also brought into question, as earlier studies showed that the effectiveness of 6-inch fire would rapidly decrease at those ranges. It would be better to provide the cruiser with an immunity zone against the newer 6-inch shell and use the weight saved to increase the firepower from twelve to fifteen guns.

In an informal hearing on March 1933, Admiral Watson proposed an arrangement with all five triple turrets mounted at the front. This would concentrate all the firepower to the forward fire control and in theory, eliminate the need for the aft superstructure and fire control. Such an arrangement would be quite baffling, but history tells us that the concept is not as implausible as some may think. In 1936, the Tone class cruisers were redesigned to have all four main battery turrets positioned forward to allow the launch of aircraft while the ship was firing. Even though the USN may not have known about Japan’s Tone class at that time, it serves as a reminder that certain designs that can be considered strange or unconventional are the result of using a different approach to solving a common problem (and in this unique case, it was a similar approach to solve a completely different issue).

USS Grand Rapids represents Watson’s idea of an all-forward arrangement, although the design itself was not officially drawn up by C&R through Schemes H, I and J after the hearing. Scheme I is likely a modified version of the idea, with four triple turrets forward and one aft. Scheme H, which had three triple turrets forward and two aft was favoured over the other designs and would eventually go on to become the final design of the Brooklyn class. The design however, did not come to an end when the last of the new light cruisers was launched in 1938; it would go on to provide the basis for the next-generation Cleveland and Baltimore classes, both of which were not subject to any treaty limitations. Indeed, it would be safe to say that if the London Naval Treaty did not limit the construction of heavy cruisers, the composition of the USN cruiser fleet would have looked very different by the end of the Second World War.

Sources

Friedman, Norman. U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. Naval Institute Press, 1984.

Lacroix, Eric., Wells, Linton. Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Chatham Publishing, 1997.

Whitley, M.J. Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Arms and Armour Press, 1996.